“But we are the only ones who can choose to listen wildlife listen to survive.” “Obviously, we aren’t the only ones listening,” Hempton told me. Intrusive sound disrupts animals’ ability to navigate, avoid predators, locate food and find mates - beaching marine life, altering birdsong and causing stress that’s linked to shorter lifespans. Research shows that the din of humanity remains pervasive in protected areas. Noise has particularly severe effects on wildlife. “One of the biggest ways that civilization creeps into wilderness is through noise.” Rather, it’s about how unnatural sounds can shatter “the sense of naturalness” essential to a wilderness experience, he said. Noise pollution in wilderness is not about loudness per se, according to Frank Turina, a program manager with the National Park Service’s Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division. “This is a national park, and natural quiet is on the list of protected natural resources,” along with native plants, historic sites and dark night skies, among other assets. “This is really incredible,” Hempton said, after Giannone tallied the noise intrusions. (Photo by James Gaither, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0) The Hoh River Valley rainforest in Olympic National Park. The Hoh met that requirement easily - until recently. By contrast, a cornerstone of the Quiet Park certification will be a noise-free interval of at least 15 minutes. Mix in the distant hum of vehicles and a chainsaw’s whine, and the longest period of unadulterated nature was just three minutes. The ambient sound averaged 25 decibels (whisper-quiet) and the peak noise, from a jet, hit nearly 70 decibels (vacuum-cleaner loud). After recording, they went over her notes.

Hempton visited the Hoh in March with Giannone, an Evergreen State College senior majoring in audio engineering and acoustic ecology, to train her in data collection for the Quiet Parks International certification. As evidence mounts that the stress of noise raises the risk of heart disease and stroke, so does interest in escaping the clamor. “Our culture has been so impacted by noise pollution,” he said, “that we have almost lost our ability to really listen.”Įverywhere, people are becoming more aware of the noise in the lives.įood critics routinely carry noise meters to restaurants, towns are banning gas-powered leaf blowers, and noise-metering apps are providing crowdsourced guides to refuges of quiet in cities worldwide.

For Hempton, the sounds of nature are as critical to a national park as its wildlife or scenic vistas, and as the world gets louder, the importance of protecting quiet refuges as places of rejuvenation grows. In 2018, he launched Quiet Parks International (QPI), to certify places that are relatively noise-free, in a bid to lure quiet-seeking tourists and thereby add economic leverage to preservation efforts. “In just a few years, this has gone from one of the quietest places on Earth to an airshow,” he told me.Īs the Hoh got noisier, rather than concede defeat, Hempton broadened his effort into a global crusade. But he couldn’t stop the sonic intrusions from ramped up commercial air traffic and the Navy’s growing fleet of “Growler” jets training over the Olympic Peninsula. In 2005, Hempton dubbed a spot deep in the Hoh “One Square Inch of Silence,” and created an eponymous foundation to raise awareness about noise pollution. Hempton has spent more than a decade fighting for quiet in this forest - the traditional homeland of the Hoh Indian Tribe, who lived here before it was a national park and now have a reservation at the mouth of the Hoh River.

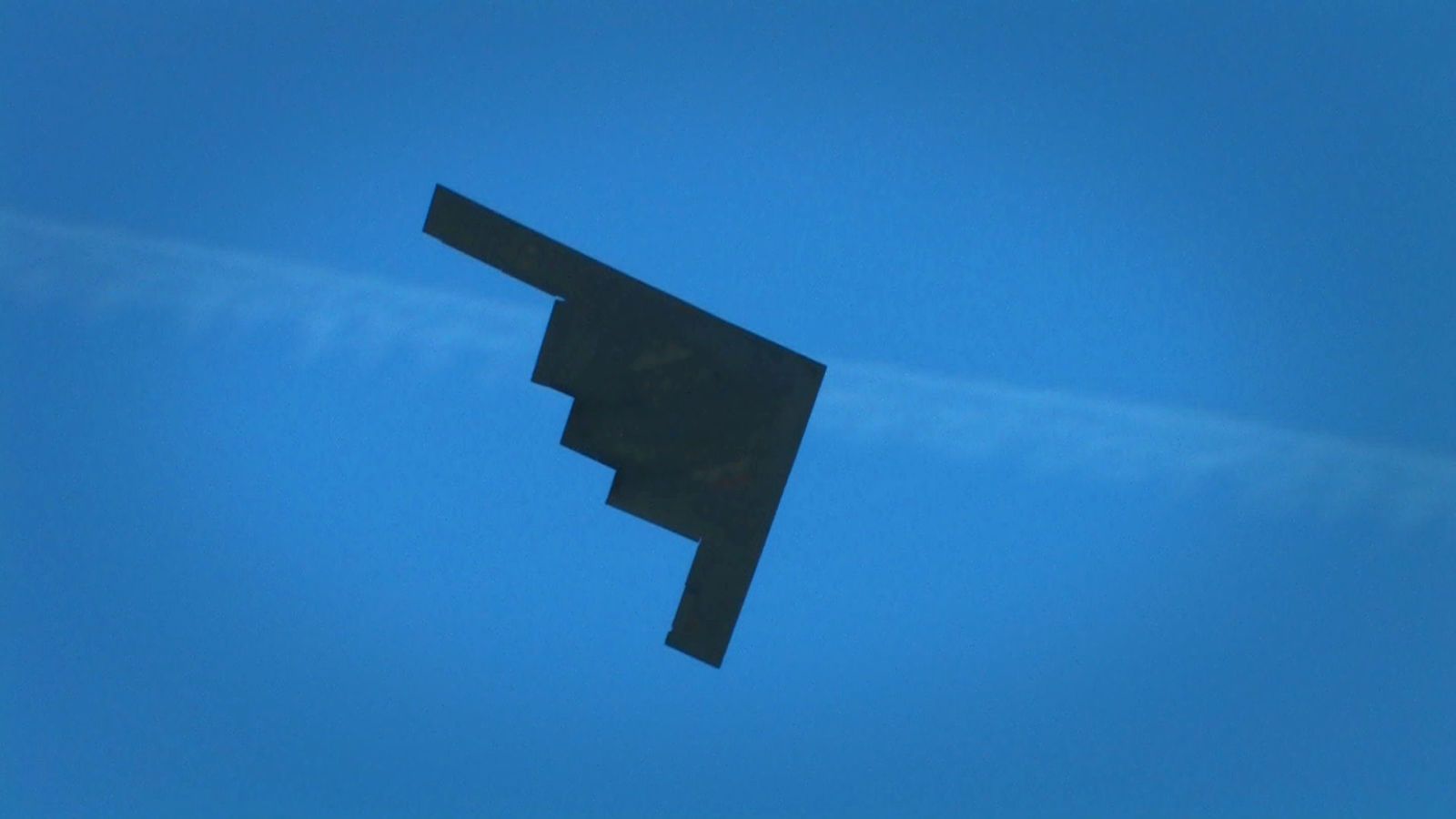

Within half an hour, three more jets roared overhead. Then, suddenly, the low thrum of a jet aircraft built in waves until it eclipsed every other sound. They set up a tripod topped with ultra-sensitive recording equipment to listen to the murmurings of a landscape just then awakening from winter dormancy.Ībove the low rush of the nearby Hoh River, the melodic trills of songbirds rippled through a still-leafless canopy. On a chilly March morning, acoustic ecologist Gordon Hempton and his assistant, Laura Giannone, hiked into a glade of moss-draped maples in the Hoh Rainforest of northwest Washington’s Olympic National Park.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)